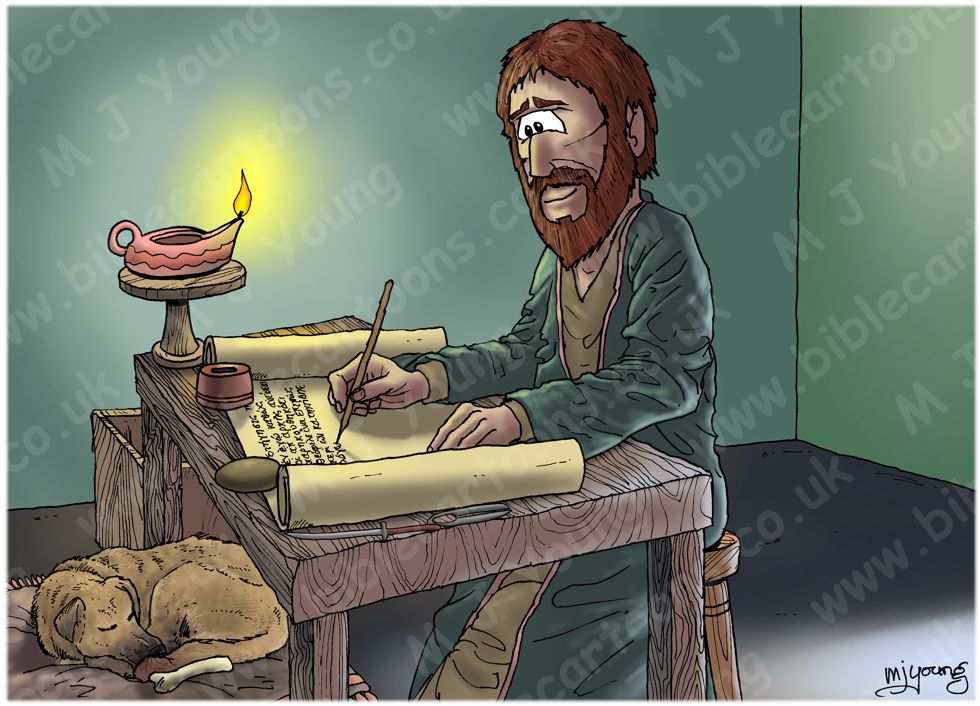

Bible Cartoon: Luke 01 - Births foretold - Scene 01 - Luke writing

Click on Add to cart button below shopping cart.

Purchased Bible Cartoons do not have watermarks. Links to Cartoons provided on email once purchase is completed.Bible Book: Luke

Bible Book Code: 4200100101

Scene no: 1 of 14

Bible Reference & Cartoon Description

Luke 1:1-4 (NLT)

1 Many people have set out to write accounts about the events that have been fulfilled among us. 2 They used the eyewitness reports circulating among us from the early disciples. [1] 3 Having carefully investigated everything from the beginning, I also have decided to write a careful account for you, most honorable Theophilus, 4 so you can be certain of the truth of everything you were taught.

[1]

Greek, from those who from the beginning were servants of the word.

DRAWING NOTES:

TIME OF DAY:

Indeterminate; Daytime.

LIGHTING NOTES:

There are two light sources in this scene 1) Warm light comes from the lamp on a stand & 2) cooler, blue/white light comes from the door (unseen) off to the right. There is thus a contrast between the warmer lamp light which throws a yellow light on to one side of objects in this scene & the sunlight which casts a cooler, bluer highlight across the right hand side of objects.

CHARACTERS PRESENT:

Luke [Doctor/Physician], his dog.

RESEARCH/ADDITIONAL NOTES:

I decided to include a dog to keep Dr. Luke company in this scene!

Notice the two surgical instruments (a thin knife & a tweezer-like tool) on the table Luke is writing on, which I included to show Luke’s physician (doctor) profession.

I looked at the beginning of Luke’s Gospel & have copied a few sentences onto his scroll, written in Greek.

Who was Luke?

The name “Luke” apparently means luminous &/or white. Although we don’t know how old Luke was when he began to write his Gospel, I have drawn him in his late 20’s. Of course we don’t know what he actually looked like, so my interpretation is purely imaginative.

‘Luke the evangelist, was a Gentile. The date and circumstances of his conversion are unknown. According to his own statement (Luke 1:2), he was not an “eye-witness and minister of the word from the beginning.” It is probable that he was a physician in Troas, and was there converted by Paul, to whom he attached himself. He accompanied him to Philippi, but did not there share his imprisonment, nor did he accompany him further after his release in his missionary journey at this time (Acts 17:1). On Paul’s third visit to Philippi (Acts 20:5, 6) we again meet with Luke, who probably had spent all the intervening time in that city, a period of seven or eight years. From this time Luke was Paul’s constant companion during his journey to Jerusalem (Acts 20:6-21:18). He again disappears from view during Paul’s imprisonment at Jerusalem and Caesarea, and only reappears when Paul sets out for Rome (Acts 27:1), whither he accompanies him (Acts 28:2, 12-16), and where he remains with him till the close of his first imprisonment (Phm 1:24; Col 4:14). The last notice of the “beloved physician” is in 2Ti 4:11.

There are many passages in Paul’s epistles, as well as in the writings of Luke, which show the extent and accuracy of his medical knowledge.’

(Source: Illustrated Bible Dictionary: And Treasury of Biblical History, Biography, Geography, Doctrine, and Literature.)

‘Luke is the only one of the four Gospel writers who stated his method and purpose at the beginning of his book. He was familiar with other writings about Jesus’ life and the message of the gospel (v. 1). His purpose was to allow Theophilus to know the certainty of the things he had been taught by writing out an orderly account (v. 3; cf. v. 1) of the events in Christ’s life.

Luke carefully identified himself with the believers (v. 1). Some have suggested that Luke may have been among the 72 Jesus sent out on the missionary journey (10:1-24) because of his notation that the things were fulfilled among us. However, the next statement that these “things” (i.e., accounts and teachings) were handed down orally by the eyewitnesses of Jesus would negate that possibility. Luke implied that he was not an eyewitness but a researcher. He was thorough and exact in his research, having investigated for his account everything from the beginning, that is, from the first of Christ’s life.

“Theophilus” (lit., “lover of God”) was a common name during the first century. Who this man was is open to conjecture. Though it has been suggested that Luke used the name for all who are “lovers of God” (i.e., the readers of his Gospel narrative), it is better to suppose that this was a real individual who was the first recipient of Luke’s Gospel and who then gave it wide circulation in the early church. Apparently he was an official of some kind, for he was called most excellent (cf. Acts 23:26; 24:3; 26:25, which use the same Gr. term, kratiste).’

(Source: The Bible Knowledge Commentary: An Exposition of the Scriptures by Dallas Seminary Faculty.)

What did Luke write on?

There are several possibilities including Vellum [1], Parchment [2] (both types of leather) & Papyrus [3], which is a reed, split & interwoven to make a writing surface.

Most commonly people used ink [4] with a pen or brush to transfer the ink to the writing surface.

Ancient Greek is written in boustrophedon style, which means one line is written & read fro left to right whilst the following line is written & read right to left. It is likely that Luke wrote in

This style became less common & the left-to-right style became standard. Ancient Greek text had no accents, punctuation or inter-word spacing, the letters all followed on, one from another.

Unlike Greek, Hebrew, Arabic & several other languages are written & read from right to left .

‘Ancient Greek is the form of Greek used during the periods of time spanning the c. 9th – 6th century BC, (known as Archaic), the c. 5th – 4th century BC (Classical), and the c. 3rd century BC – 6th century AD (Hellenistic) in ancient Greece and the ancient world. It was predated in the 2nd millennium BC by Mycenaean Greek. The language of the Hellenistic phase is known as Koine (common) or Biblical Greek, while the language from the late period onward features no considerable differences from Medieval Greek. Koine is regarded as a separate historical stage of its own, although in its earlier form, it closely resembled the Classical. Prior to the Koine period, Greek of the classic and earlier periods included several regional dialects.

“Biblical Koine” refers to the varieties of Koine Greek used in the Greek Bible and related texts. Its main sources are:

the Septuagint, a 3rd-century BC Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible and texts not included in the Hebrew Bible;

the Greek New Testament, compiled originally in Greek.’

(Source: Wikipedia)

Based on the above, dr. Luke would most probably have written in Koine (common) or Biblical Greek, since he was alive during the Hellenistic period.

[1]

Vellum

Derived from the Latin word “vitulinum” meaning “made from calf”; fine calf skin leather.

‘Vellum is simply a fine quality of leather prepared for writing on both sides. The autographs of the New Testament were most likely written on papyrus, rather than leather or vellum, but most of the earliest codices and all, until recent discoveries, were on this material, while very few of the long list of manuscripts on which the New Testament text is founded are on any other material. This material is referred to as parchment by Paul (2 Tim. 4:13). Almost every kind of skin (leather or vellum) has been used for writing, including snake skin and human skin. The palimpsest is secondhand or erased vellum, written upon again.’

(Source: The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia.)

[2]

Parchment

(μεμβράνα, membrána (2 Tim. 4:13)): The word “parchment “which occurs only once (2 Tim. 4:13), is derived from Latin pergamena (Greek Περγαμενή, Pergamené), i.e. pertaining to Pergamum, the name of an ancient city in Asia Minor where, it is believed, parchment was first used. Parchment is made from the skins of sheep, goats or young calves. The hair and fleshy portions of the skin are removed as in tanning by first soaking in lime and then dehairing, scraping and washing. The skin is then stretched on a frame and treated with powdered chalk, or other absorptive agent, to remove the fatty substances, and is then dried. It is finally given a smooth surface by rubbing with powdered pumice. Parchment was extensively used at the time of the early Christians for scrolls, legal documents, etc., having replaced papyrus for that purpose. It was no doubt used at even a much earlier time. The roll mentioned in Jeremiah 36 may have been of parchment. Scrolls were later replaced by codices of the same material. After the arabs introduced paper, parchment was still used for centuries for the book bindings. Diplomas printed on “sheepskins,” still issued by many universities, represent the survival of an ancient use of parchment.’

(Source: The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia.)

[3]

Papyrus

‘Papyrus was not only the chief of the vegetable materials of antiquity, but it has perhaps the longest record of characteristic general use of anything except stone. The papyrus was made from a reed cultivated chiefly in Egypt, but having a variety found also in Syria, according to Theophrastus. The papyrus reed grows in the marshes and in stagnant pools; is at best about the thickness of one’s arm, and grows to the height of at most from 12 to 15 feet. It was probably a pool of these papyrus reeds (“flags”) in which Moses was hidden (Exodus 3:3), and the ark of bulrushes was evidently a small boat or chest made from papyrus reeds, as many of the Egyptian boats were. These boats are referred to in Isaiah 18:2.

Papyrus was made by slicing the reed and laying the pieces crosswise, moistening with sticky water, and pressing or pounding together. The breadth of the manufactured article varied from 5 inches, and under, to 9 1/4 in., or even to a foot or a foot and a half. The earliest Egyptian papyrus ran from 6 to 14 in. Egyptian papyri run to 80, 90 and even 135 ft. in length, but the later papyri are generally from 1 to 10 ft. long. The use of papyrus dates from before 2700 BC at latest.

Many Bible fragments important for textual criticism have been discovered in Egypt in late years. These, together with the light which other papyri throw on Hellenistic Greek and various paleographical and historical problems, make the study of papyri, which has been erected into an independent science, one of very great importance as to Biblical history and Biblical criticism (compare Mitteis u. Wilcken, Grundzuge …. d. Papyruskunde, Leipzig, 1912, 2 volumes in 4). It has been argued from Jeremiah 36:23 that the book which the king cut up section by section and threw on the fire was papyrus. This argument is vigorously opposed by Blau (14, 15), but the fact of the use of papyrus seems to be confirmed by the tale that the Romans wrapped the Jewish school children in their study rolls and burned them (Ta`anith 69a, quoted by Blau, 41). Leather would have been poor burning material in either case. Certainly “papyrus” is freely used by the Septuagint translators and the word biblíon is (correctly) translated by Jerome (Tobit 7:14) by charta. It is referred to in 2 John 1:12, “paper and ink,” as the natural material for letter-writing.’

(Source: The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia.)

[4]

Ink

Of the many materials used in order to lay one contrasting color on another, the flowing substances, paint and ink, are the most common. In general throughout antiquity the ink was dry ink and moistened when needed for writing. Quite early, however, the liquid inks were formed with the use of gall nut or acid, and many recipes and formulas used during the Middle Ages are preserved. See INK, INK-HORN. The reading of a palimpsest often depends on the kind of ink originally used and the possibility of reviving by reagents.

(Source: The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia.)